The ulcer- inducing, far-right plan for how to remake society, Project 2025, has been circulating widely. What the plan outlines with regard to the work I do has been a cause for alarm for some time (i.e., gut climate protections, devastate the EPA, encourage even further consolidation of agribusiness and dismantle human and natural rights, making small farming impossible.) The sickening plan has been waiting in the wings; it’s important that people are shining a light directly on it.

And. I’ve increasingly held the question (and now seen others discussing it online, thankfully!): well, what is OUR plan?

What is the core goal that we [who believe in freedom] can all articulate with ease? What is our clear and simple vision, paired with a winnable roadmap to achieve?

The goals of the left are often described as more intersectional, more complex, less reductive, somehow tricky to express. But… is that true? Perhaps seeing our goals as too complex to be summarized is more about the fact that our educational system and culture have taught us more often how to critique than build, more to problematize than imagine or inspire.

Tech bro and AI enthusiast Mark Zuckerberg asks his team to “move fast and break things” while Indigenous systems thinker and life enthusiast Tyson Yunkaporta points out how “it’s way easier to break shit than make shit.”

So, we need to put on some Beyonce, squad up, and start getting highly organized and Get. In. formation. What might that look like? Find a power building organization and get involved. Find trustworthy leaders, ask what they need help with, and join their plans. Build a mailing list of everyone you know and set up mutual aid systems. Gather up your neighbors, as what is keeping them up in the night. Write those answers down, break them down into action steps. Take the first step.

Project 2025 is a thirty year strategy that has gotten slowly enacted step by step. We need to get much, much more disciplined– and also more practiced at articulating what we are FOR.

I want to suggest our efforts, perhaps, could be just as simple as the far rights’ message. Big picture, we are reclaiming what pro- life means. We are working for life. Beyond borders. For people, and the planet. Life beyond capitalism. Outside of prisons. Where people and planet have rights, not corporations. L’chaim— to life.

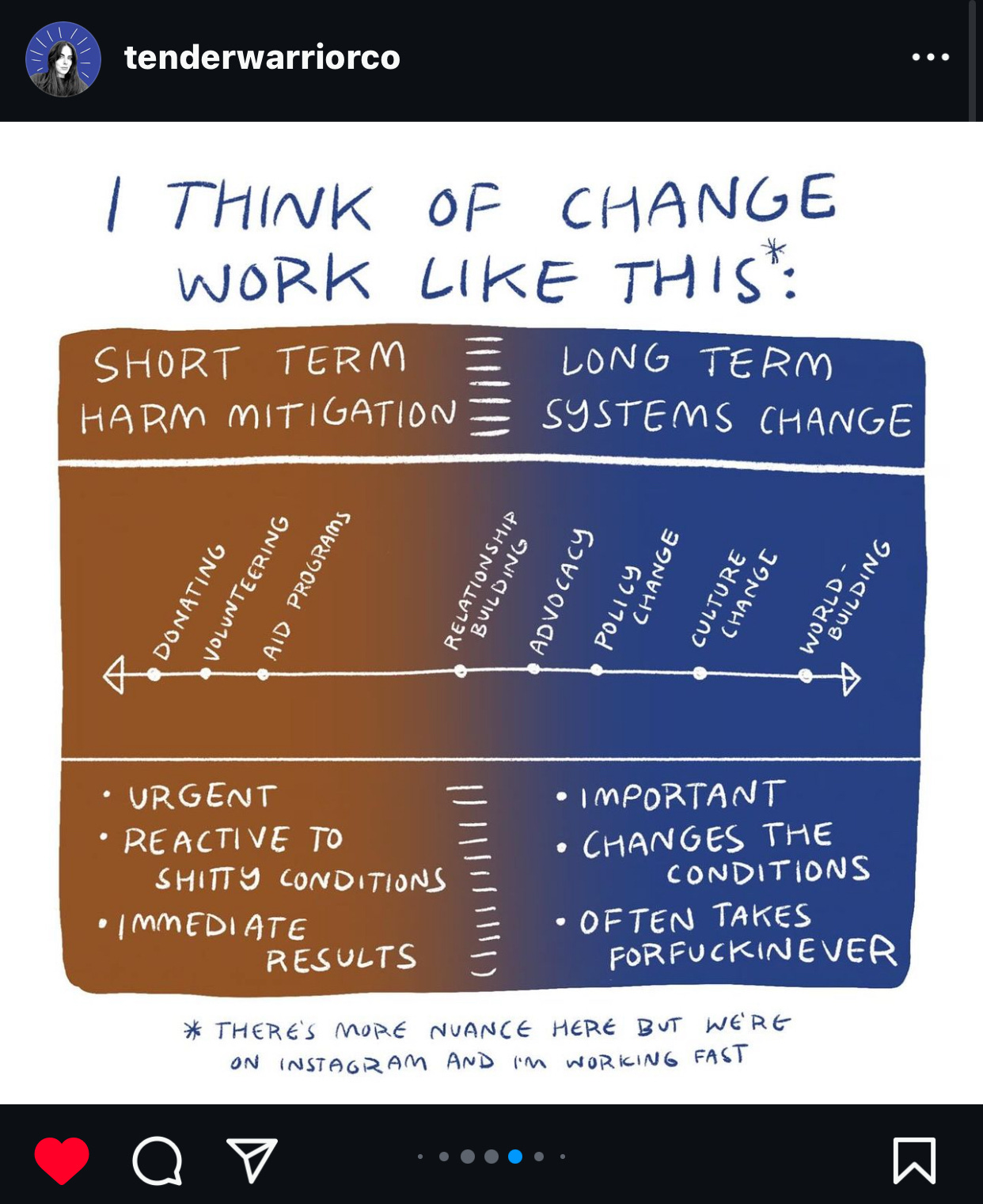

My brilliant friend Christine (@tenderwarriorco– artist/ organizer/ visual genius– you should follow her immediately!) recently made this awesome graph that shows how the range of change work, from transformative and radical overhaul of systems on one side and harm mitigation in the systems we have on the other. My takeaway is: IT IS ALL NEEDED. There is no “right” kind of helping to do. We all need to find our place and take it up.

Right now in the short term we must reduce the worst harms while we continue planting seeds for the world we need. We all have a unique position we can work from, and we are called to do so now.

Here in Vermont, we just had a second year of epic flooding, on the literal anniversary of last years “centennial flood.” Harm reduction work in this case, looked like literally hundreds of people pouring onto farms to help farmers pull crops out of fields as the river gauges revealed that the banks would soon be breached. Short term response work looked like calling out of work to be there, like making donuts and tea to feed the crews hauling the new potatoes out, and up, away from the encroaching water. It looks this week like clean up, or hosting someone in your house whose apartment washed away.

I remembered being at a La Via Campesina encuentro gathering and hearing from farmers in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. They described big crews walking farm to farm to check on each other, helping each other make it through the season, making sure elders had food and water. I wondered: could we pull that off here? It was hard to imagine. But last week— we did. The grassroots flood response here was so profound to witness. Yes, in times of crisis people can crack or splinter apart. But more often: they rise up together. They get resilient. In fact, this is what marginalized people surviving within a system designed to oppress them have had to know how to do forever. As Mia Birdsong wrote, “People do not survive racism, xenophobia, gender discrimination, and poverty without developing extraordinary skills, systems, and practices of support. And in doing so, they carve a path for everyone else.”

We all have resilience and possibility in us when we learn and listen deeply to those who have more experience with survival. Even now, even feeling tired: we have what it takes to do what is needed.

In the long term, change work looks like building power with small farmers and community members who lost their livelihoods through organizations to raise our shared voices. It looks like taking over under-tended or poorly utilized lands, and growing there. It looks like planting tree crops that take seventy years or three hundred years to harvest. It looks like reclaiming religious spaces from nationalism. It looks like a lot of work whose fruits we likely won’t see in our lifetime. It’s hard, long term work— but it’s also work that will give our lives purpose, meaning, hope.

And if you’re afraid of what that will take? You still just do it, scared.

One of the best things I have learned from birthing multiple children— and other supporting people through birthing many times— is that fear is often a player in a transformative, emergent process. Sometimes, we can find tools to overcome that fear. But more often, we have to work with our fear.

Right now, we just have to have the fear right there with us (what if Trump does get reelected, and then won’t leave? What if the ice caps melt too fast? What if we’re too late to make anything better? What if we don’t have what it takes to stop the war? What if we look like an idiot? What if we fail? What if our religious community disowns us? What if our art goes nowhere? What if none of this matters?) These fears are real and valid and not wrong, but also: not necessarily right, or helpful. They are the worst scenario appearing, trying to keep you safe.

You can acknowledge those fears and then: you move ahead anyway.

Seth Godin says it plain: “It’s always your turn.” So, you take your turn.

And.

At the same time we must take ourselves seriously as people with power and agency who can affect change– which we are, and we must– we have to simultaneously hold the opposite truth, too: actually, we control very little. We practice and engage spiritual discipline to do the inner work to both work rigorously and also to let it go. Or as somebody's grandma used to say when I lived as a small child in Macon, GA: give it to God, honey. Give that all up to God.

Recently, my eight year old was reading a book about evolution and extinction eras, (why do kids books just really tell it like it is sometimes?!) and asked me how come humans had made all the passenger pigeons die. He looked troubled and sad. I felt something close to clarity flow through when I said plainly: 'oof, Amos, I know. There is really so much that’s been done that has caused all kinds of harm. It’s hard, and it’s so, so sad to know about all that has happened sometimes.

And also– (and I looked at him in the eyes and meant it when I said) – ‘The good thing about being alive now is we get to be one of many generations who are going to help. We get to work to figure out what repair is needed now, and we get to make it right. That is a really special and important job we have. That other people before us did too.’ For now, at eight, he accepted this idea.

In other words: “it is not ours to complete the work, but neither are we free to desist from it.” (Pirke Avot.) Or perhaps Heschel, “Few are guilty, all are responsible.” Or from adrienne maree brown, “I am living a life I won’t regret.”

I trust us all to be able to hold this complexity. We can build beautiful networks of care right now– even as we face devastating grief– so much loss, so much horror, so much fear. And it’s our turn, and it’s been others turns before. So we take our turn and step up to whatever point on Christine’s graph you can. All are needed.

But, since we’re talking about grief– I’m going to pivot to something a little more Jewish- text- y now in that vein. Please do feel free to stop reading if you are not into it! You get a Hall pass on Talmud Torah! For those of you feel like an old warning story about unprocessed grief might be called for right now, proceed on.

Last week we read Parshah Chukat, a Torah portion that truly has a lot packed in: instructions for how to become clean after touching a dead body (spoiler: it involves a perfect red cow and is quite wild!); the death of Miriam, Moses’s sister who led people out of through the desert and was able to locate water miraculously; the lack of water that follows her death; the people’s thirst and struggle with their journey; Moses getting angry and hitting a rock that Gd tells him to speak to; Aaron, another key leader’s death; battles; still more travel– and a lot, lot of struggle between the people and the leadership.

If you haven’t read Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg’s recent piece about Christian Zionism and the Red Heifer, you should absolutely do that before you read anything else about this parsha. In it Rabbi Ruttenberg connects how this funky, old chukkim - style law (that is, a law that while it’s required by G-d, really doesn’t make sense on its own two feet; a category in counterpose to the laws that make more sense just as common sense ideas, like the prohibition on killing or stealing) with Christian Zionists. She explains, through the lens of the Red Heifers, Christian Zionists are using the nation state of Israel for their own religious purposes. (As my friend Dr. Ilyse Morgenstein- Fuerst would say: Religion: definitely not done with us!)

But the element I mainly want to focus on from this week’s story is the moment when Moses yells at the people. I’m curious about why now he gets to this place of uncontrolled rage. The wandering people are in the desert and have (again) been complaining. But this time, their complaints seems legitimate. Having recently lost Miriam ( the person who could bring water to the desert and also songs and uplift) they have no water now in the desert, and the soil is “no place to plant a seed.” In some ways, their lamentations have often felt like a “boy who cries wolf” situation. The people have been so whiny, missing their food from Egypt, but now their concerns are real. Water…is a survival issue. Moses is so worn thin, so frustrated and tired and unable to hear one more whine, and he basically throws a massive tantrum.

Moses shouts in an outburst: "Listen, you rebels, shall we bring water for you out of this rock?" (Numbers 20:10) With the term "rebels" he reveals his contempt and anger for his own people, a sure sign of a leader at the brink. Moses, who had devotedly led the people and interceded to Gd on their behalf numerous times, is ragged, and is OVER IT.

So, why is this the moment he breaks? Well, perhaps what is unsaid in the text is what is most important. Moses has just suffered the grief of losing his sister, which has largely gone unprocessed. The text skims over her death, weirdly quiet for such a front and center figure. The line reads only, “and the people abode in Kadesh; and Miriam died there, and was buried there.”

Virtually no time at all is given to holding space for Miriam, the person who led the people through the parted sea with song? The person who brought water through the desert, anywhere she went, ensuring safety? The person who offered supervision and wisdom and counsel when needed?

When we don’t make space to grieve, we rage. And when we rage, we do stupid, harmful things. We strike the earth, we harm it. We yell at the people we’re supposed to be supporting, we harm each other. We transgress our most holy duties, we harm the divine. We profane the earth, and ultimately we (well, Moses in this case) lose entry to the land of freedom he was seeking.

I read this text like a warning for our time: make space to grieve, or risk it all.

How can we make space to grieve so that we are able to move into the work (both short and long term) that is needed? How can we allow grief to be a generative and healing force? How can we design supportive communities to contain that grief? Climate crisis is here. Violence and starvation are being done in our name and with our tax dollars. These things require grief. They are hard, they are awful. To grieve them is to remain human.

And. To grieve them allows us to move into a different place. Instead of a place of lashing out anger, we can access another path. A path that is discerning. A path wide enough to hold also the beauty in the world, here still. The possibility of our agency when we come together. The permission to be small and tiny and insignificant, laying under a massive blanket of stars. To be accountable to all that means, and to let our responsibility end where it actually does. That is: to be human.

My friend Adam, a farmer, (who gives away all the food he grows, living in a deep experiment around gift economy) who also writes a substack newsletter weekly sent one out this week called “So much noise, so little song.” In it Adam wrote,

I have a hunch that how we raise our voices matters much more than we’d like to believe. In every moment the road forks three ways: grief, grievance and gratitude. To say, “I am in pain” weaves a different cloth than “Those people hurt me.” To say, “Even in this much pain, I can hear the world singing,” allows for the possibility of healing. To say, “I am alive today alongside millions of miraculous others” might let the pain to slip into the background for a few precious moments.

In the wake of the flooding, I find that the only place big enough to hold my grief is the earth itself. I’ve been going outside more, submerging in the rivers that aren’t too high as often as I can. I’ve been running my hands along the raspberries in my garden, so plump and soft and red, saying out loud to them, “thank you, thank you berries for tasting so so good” before I put them into my daughters mouth for breakfast. The earth can hold my grief, can take it down and transform it in the soil layer back out into something useful.

We always have enough time, when we’re collaborating with the earth, when we’re still living, still here.

We only have to get into formation, and then give it all over, give it all up.