Any conversation I start these days has to go something like: it is all too much to hold right now. There is just so much pain to process, so much direct trauma and violence we’re witnessing. First, I hope you can find spaces that feel healing, connective and values- aligned, like this virtual multi-faith prayer space being held on Sunday, to center and calm. I hope you can go be outside and put your hands deep into some soil, can plant a sapling this weekend. I hope you can talk with a trusted friend, spend time drinking tea. I loved this podcast‘s recent discussion about how we are all a collective body, and our peak points of life—a very moving concert, a powerful, gathering action, or communing in nature – all are moments that help us to dissolve our concept of our self into a much larger whole. We can’t survive alone, and we all need to find practices of shared calm so we can move with the clearest heads possible for peace.

As I write about what is unfolding in our nation and around the globe, I’m not going to argue why the protests are deeply hopeful and necessary, even if sometimes their language makes you uncomfortable, Peter Beinart already did it. I’m not going to explain how moral panic has been intentionally whipped into a frenzy to allow for militarized, oppressive crackdowns on peaceful student protestors, Jewish Currents already did it. I’m not going to research the history of student protest and with the same tropes reasserted to disparage them every time, the Zinn Education Project is doing an excellent job. I’m not sharing photographs of starved, orphaned, maimed, bombed children and babies covered in dust and blood, as I worry people choose to look away instead of processing the horror. I will honor the many excellent people on the ground, like Bisan Owda, who are taking footage in real time as witness, as protest, prayer, testimony- and suggest that if you haven’t made yourself the space and time to take in what is being done to children, if you haven’t believed or can’t bear to look, please make space give them witness. And allow that witness move you to action. To act as if these children were your children, as James Baldwin (z”l) wrote, “The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe.”

Instead, tonight I want to spend time writing about what we are moving towards. Martin Luther King Jr taught that “the aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community, while the aftermath of the violence is tragic bitterness.” Of course relentless violence and dehumanization will result in nothing other than increased violence and dehumanization. But perhaps the way we show up to our resistance spaces could actually move us closer towards beloved community – which he defined as a “society where caring and compassion drive political policies.”

In my Judaism, olam haba (a term for the world to come, the world we long for and know is possible) could be seen as beloved community. But the is too often constructed as a far- off impossibility, like heaven, an ideal world that will never be reached in our lifetimes. What if olam haba is not a final place we arrive, but rather the shine of it flashes out in small moments, thrown off like sparks from a flint stone. What if we are co-creators of olam haba through our actions, by moving towards wholeness and care.

Martin Buber wrote that “all life is meeting.” We are always meeting each other, meeting ourselves, and ultimately meeting the divine in these very moments, these unfortunate ones right here! How we choose to engage or disengage, fight or learn, feed or starve-- will move us towards meeting something. What do we want to meet? What are we collaborating to birth? We are making something with each act. Are we healing or harming?

In a time of urgency, there are a lot of pulls to be everywhere and do everything. I’m working on my discernment. I’ve been trying to tune in what spaces feel like they are rehashing old ideas or actually move us closer towards beloved community. I’ve been trying to notice also what specific activities I’m doing when I feel that a sense of wholeness and care-- even in a fleeting moment.

What makes a space holy? And what do I bring that adds holiness?

I led a liberation and solidarity seder during Pesach last week. Quite last minute, we offered to host and had eighty people in a giant circle. People all took turns leading, children standing on chairs to be heard. Elders leading us in Miriam’s Song, the song of the Red Sea parting in the Exodus story, the people working through their fear by dancing through it. The affirmation of a story about what felt impossible becoming possible when people moved together with faith. (Here is our haggadah if you want to peruse—always open source everything.) We wove new meaning into old traditions (olives on seder plates alongside shank bones harvested from friends’ farms, donations to Palestinian kids for food when our children were hunting the afikomen). The night felt like a taste of possibility, of what community that weaves together values and tradition, prayer and action, in one whole.

And we sang. We took turns leading prayer songs and protest songs, peace songs with liberation songs, funny old songs and songs of death and grief. When I looked around the room I saw people breathing together, and making harmony.

I clarified an organizing principle: move towards the people who are singing. They may carry a song of grief, or lament, or protest, but the people singing are those to listen to. People singing have found a way to be calm enough to breathe, to pause. To consider. People singing have committed, together, to make something beautiful.

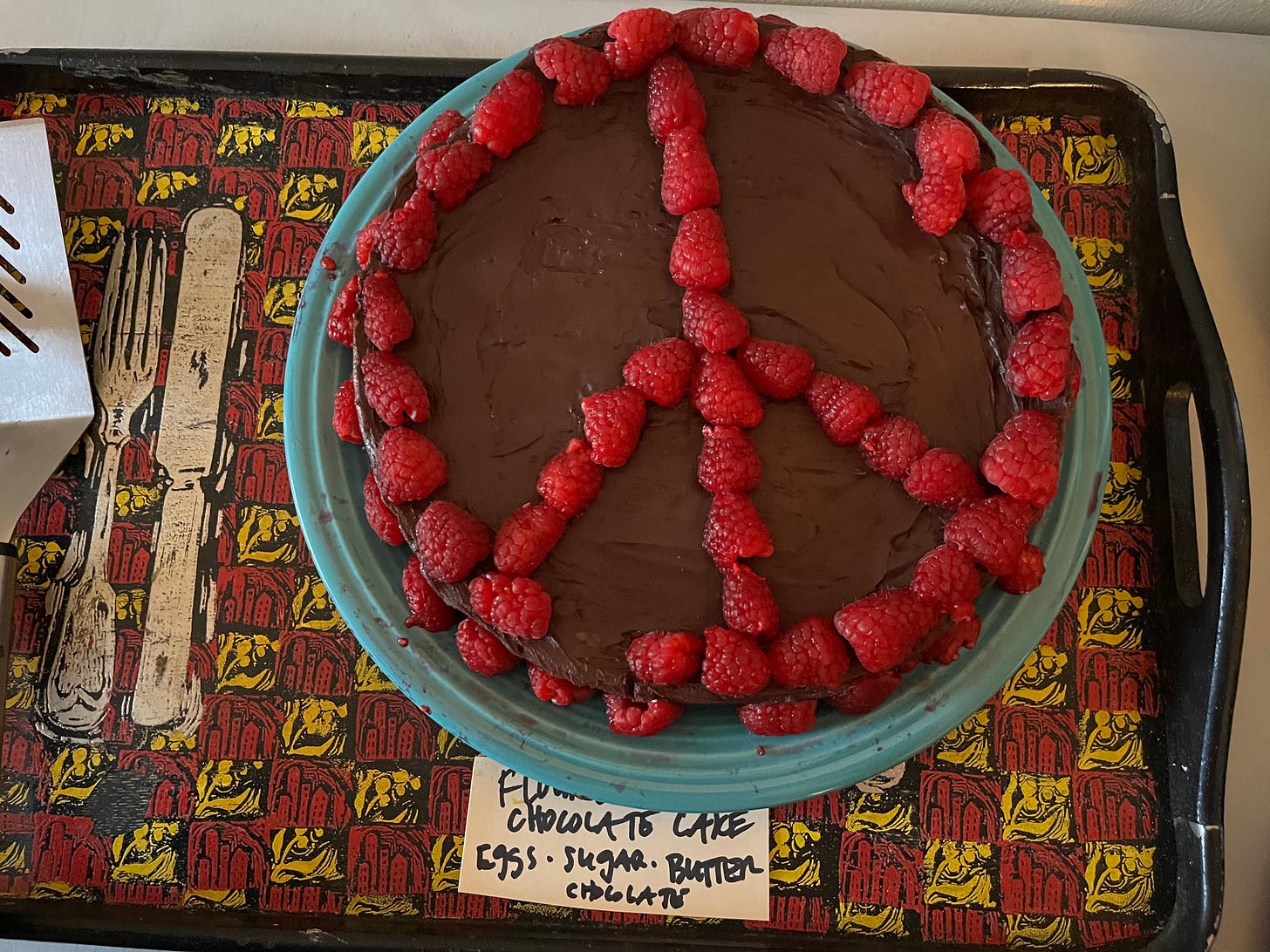

Then this week the UVM student protestors established their encampment. I had just witnessed a friend of a friend beaten at Emory, and seen another close friend arrested in Israel trying to walk aid into Gaza, to literally observe the call in the seder of הָא לַחְמָא עַנְיָא / ha lachma anya which means ‘May all who are hungry, come and eat.’ I felt so tenderly and fearfully the real risk for the students who are choosing to stand up right now. I immediately knew I wanted to feed them. I wanted to feed them something delicious and familiar and appropriate for the holiday, and I decided to bring them the best Passover treat: Smitten Kitchen’s matzah toffee. I enlisted my children in the cooking, and we talked about the history of student protests while laying out the matzah and bubbling the caramel, the kitchen smelling of warm vanilla and brown sugar. The feeling of coziness and safety of cooking with ones children: this is what I want for everyone to have. This is what I know is possible.

As the toffee was cooling Zusa asked me calmly, “mama, is your job to bring candy to protests?” I laughed, and then she reminded how when I left for the Pilgrimage for Peace from Philly to DC, I packed a bag with maple candies and big chocolate bars to bring for the pilgrims walking with me. She retold me the story I had shared about how we had all stopped to eat milkshakes after long days of walking miles, ‘praying with our feet.’ “Well, maybe bringing some sweetness is at least a piece of my job,” I told her. “Maybe that’s it.”

It’s not that I want saccharine. I want to be where people are feeding each other, where food is abundant and there is a place for everyone at the table. Where someone brought the good butter, made the cake from scratch. I want us to aim for the joy of dessert on top of a meal: I want to us to cultivate towards moments of possibility and joy, all tucked into the struggle. I think of Mary Oliver’s ‘joy is not meant to be a crumb.’ (Zusa’s name is the first on our family tree on a literal scroll going hundreds of years back. Zusa is Yiddish for ‘sweetness’, but it also sounds a hell of a lot like ‘Zeus’. The mix of sweet and unbridled strength serves my daughter, and all of us, well.)

When I got to the student encampment, there was a long table literally bowing with food, with volunteers organizing plates and distributing bowls of hot soup.

Almost two decades ago, I worked as doing translation for a union for sex workers in rural India. They had organized as a union to build power against police violence and protect each other’s safety at the height of the AIDS crisis. I learned so much about community organizing, about leadership by and for the people. I learned how to listen, even when the mix of languages exceeded my grasp and to let the sounds and body language speak. I learned about what it meant to commit to a strategy that took decades to unfold. I learned about what kind of power those most marginalized in society could build when they came together. I learned especially about the role of joy in movement spaces, even in really hard times, when the union’s members would throw massive, days-long organizing meetings/fashion shows/ feasts where food was cooked in pots as large as a bathtub and stirred with an oar.

At one point I had to cross the country on a train for work, from rural Kolhapur on one side of the country to Delhi on the other. It became clear quickly that I hadn’t packed enough food for what ended up being a three-day trip. After the first day I ran out of my meager bars and fruit. The second day, a kind elderly couple seated across from me had continued to pull out tiffin after tiffin (the metal stacked lunch boxes) of beautifully cooked whole meals, complete with rice and chapatis folded neatly. They had come prepared. They had brought more than enough.

They started feeding me after seeing me miss a couple of meals, communicating an invite across our jagged patchwork conversation stitched together with scraps of regional languages. After the day, the couple got up to leave before I did, and took down a giant box. They were traveling to their own son’s wedding and had prepared special homemade desserts of ghee and coconut sugar for the festivities. Without pausing, they handed me the entire box, hugged me, and disembarked. I didn’t even have their names or where to thank them. That box sustained me for days, and the feeling of being given something so important and special so graciously and generously, was a uniquely life- affirming experience of being deeply cared for by the whole. ‘Of resting in the grace of the world’ (Wendell Berry). Of humans being good. A true meeting holiness, spark from olam haba.

I am working to stop anticipating ever getting to some arrival. I’m trying to embrace that we’re always really trip leaders, packing for the journey of justice. It’s unlikely that we will see an end in our lifetimes to injustice and struggle. We just need to keep making food ahead for the train rides, and maybe someone else’s too. We need to keep singing, and learning to harmonize. We are always moving through changing conditions, confronted with world forces and others actions. We can only choose what kind of path we make by how we walk. How we stay committed to our values despite shifting ground. And how as we travel, we make beloved community. Community that gives us strength to face the reality of what is happening, and meet the moment with presence.

As we sing together, as we feed each other, as we commit to the hard, rigorous work of peacemaking, we create holiness, even as we struggle and face of violence. As we strengthen communities committed to nonviolence and to care, we create the world we need, even if for just the moments of meeting. What else do we have?

.